Because so many people come to this blog for tips on hosting a Victorian-style dinner, I thought this would fit right in. It’s from an article I read recently describing the fashions of serving food and laying tables in the 19th century.

“Dinner Old English style, which actually originated in the 18th century, referred to the style of placing all food items on the table before the diners sat down. In this service, guests could help themselves to the food items set out before them, within the bounds of proper manners. Where servants were unavailable it was considered, by some writers as late as the 1870s, “acceptable” behavior to help oneself to any dish on the table within reach. This service changed throughout the 19th century, taking on bits and pieces of other styles.

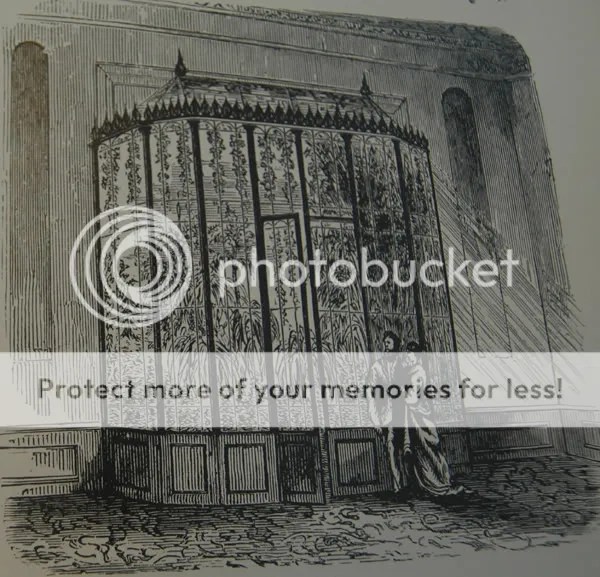

A departure from the Old English style called for food items to be replaced by decorative centerpieces. This style was commonly referred to as à la Russe in late 19th-century guidebooks. Serving dinner à la Russe became fashionable among European elites during the 1850s and 1860s, and by the 1870s it has also become fashionable in the United States.” (82)

Because the high cost of employing the many servants that were needed for the dinner à la Russe, and the shortage of good servants at the end of the 19th century, a new style called American style arose. “In the American dinner service the table was laid in the same manner as that of the à la Russe style, the major difference between the two was that the American style required the host and hostess to divide food portions on individual plates and then pass them or have them passed around the table by a servant. Food items from each separate course were placed on the table and then served from there or a side table.” (83)

How a table looks like is described here by describing a boarding-house table: “If the table is void of flowers, and other side decorations, including olves, rashishes, and celery, tastefully arranged napkins and wineglasses, an impression is given os a boarding-house table.” (84)

When the courses grew larger in number, the plates grew smaller to accommodate the smaller portions served. At the end of the 19th century, plates were on average 2 inch smaller in diameter than earlier on in the century.

(All info and citations from “A la Russe, à la Pell-Mell, or à la Practical: Ideology and Compromise at the Late Nineteenth-Century Dinner Table” by Michael T. Lucas, which appeared in Historical Archaeology, Vol. 28, No. 4, 1994.

Want to read more on Victorian dinners? Check out these books on amazon:

victorian dinners

>

> >

>

Hi! My name is Geerte, I'm a researcher of Nineteenth century history from the Netherlands. This blog is where I write about my favourite subject. Feel free to browse around!

Hi! My name is Geerte, I'm a researcher of Nineteenth century history from the Netherlands. This blog is where I write about my favourite subject. Feel free to browse around!